As storytellers we’re led to believe that people don’t have attention spans anymore. That their patience is blown out like the elastic in an old pair of tighty-whities. We’re cautioned to give readers no time to bow out. We have to grab them by their short-and-curlies right out of the gate or they’ll bail after five pages to go take a dirty Snapchat of themselves Vine-ing their latest game of Candy Crush.

And so we caution one another as writers to begin fast, go in hard, start with action. In the first five pages we need mystery and karate and explosions, maybe a car chase or three. Gotta be bodies on the ground. Fire in the jungle. Apocalyptic fol-de-rol. The promise of the premise punched into the brain of the reader. (This is told to screenwriters, too, though folks seem to forget that even with a high-octane damn-near-perfect action movie like Die Hard we get a whole first act full of toe exercises, domestic tension, and corporate socializing, devoid of Gruber-led terrorists.)

It’s not just about beginnings, either. A lot of advice seems to caution against letting a book breathe, letting it have oxygen. Even the (frankly horseshit) Freytag’s triangle is a straight escalating line—no peaks and valleys, no pockets of air. Just a straight roller coaster climb to the top, then a sharp decline toward the death of the story. Game over, goodbye.

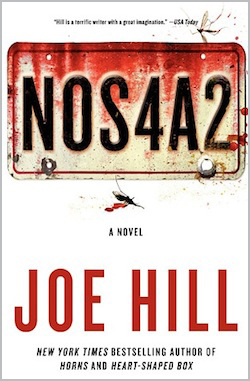

So it is that we come to Joe Hill’s NOS4A2, a book apropos to the season—kind of a thematic Nightmare Before Christmas on Elm Street that mashes up the Halloweentown sensibilities of Freddy Krueger with the quaint holiday tinkle of Christmastime.

It’s worth noting that a truly great book often seems to transcend a writer’s ability to read it purely for craft awareness. The mechanics of an amazing book are transparent. You don’t need to see how the microwave works; it just works, damnit. Sometimes you have to squint extra-hard as a writer to see what’s really going on.

This is true of NOS4A2, which is such a fine read you lose yourself within it—you can only see trees, no forest. But after reading it, I thought to look back at it and here’s the thing:

It’s a big damn book.

And, in theory, it’s a slow book, too.

Note that I didn’t say boring. Don’t mistake those two as being synonyms for one another.

This is a 700-page horror epic and it while by the end it’s got a blistering pace, in the beginning it takes its time to introduce us to the character of Vic, to her family, to the mystery of Charlie Manx and to the strangeness of the Shorter Way. Sometimes the book meanders a little bit, takes a shortcut here, a side road there.

Those roads always find their way back. And it’s tempting—and a hair bit lazy—to say that these are just digressions. Interesting, you might think, but non-essential.

Except, they’re completely essential. We get to know the texture of the world and come not only to recognize the plight of the characters but to know them the way you know your own friends, your family, even yourself.

The book takes its time. It fills the story with oxygen—oxygen that the story sometimes has to set on fire to burn everything in it, because that’s just how this tale goes what with Charlie Manx and his joyrides to Christmasland. This is a story in the hands of a confident storyteller. Confident in his own ability to write it.

And confident in our ability as readers to stick with it.

That’s not to say that every book is going to be like this, or need this—Hill’s own Heart-Shaped Box really does set up a bitchin’ pace right from the get-go, covering in the first 100 pages what you think would take the whole 300.

I’m often wont to say that I like a story that doesn’t fuck around, but now I’m thinking that’s not necessarily true. Because this book? It does fuck around a little bit. It’s roomy. It’s got legs. And I start to think that a lot of my favorite stories fucked around quite a lot: The Wire, or Breaking Bad, or the diptych of epic apocalyptic horror novels: Robert McCammon’s Swan Song and Stephen King’s The Stand.

Sometimes, we writers gotta give a story the space it needs.

And we have to trust that the readers will give it that space, too.

NOS4A2 is available from Harper Collins

Chuck Wendig is a novelist, screenwriter, and game designer. He talks a lot about writing. And food. And the madness of toddlers. He uses lots of naughty language.

I’ve been meaning to check this out, I’ve heard nothing but good things about it.

Well said, sir. I couldn’t agree more.

It was fantastic… I highly recommend the audio book!

I disagree – this book was a massive disappointment. And slow. And boring – most of the time. There are moments of brilliance, but when you describe one lengthy event in real time in one chapter, then describe the same (lengthy) event from another character’s POV in the next chapter, and then describe the same (Jesus, come on!) event again from another character’s POV in the next (albeit shorter) chapter, you will find your book in my “donate to Goodwill” bin. Your apologistic comments have been noted, however, and thank you.

I’m 3/4 of the way through this book right now. Assigned reading for my MFA in popular fiction program, but I would have read it anyway. It’s brilliant and funny and sad and creepy and wonderful. Long, yes, but enjoyably long like a road trip with detours to see creepy funhouse attractions. It’s also, I might add, a fantastic look at mixed blessing (curse?) of leading a life where you access worlds beyond the mundane, i.e. being a writer.

NOS4A2 is my best book of the year (and there’s not much time left for anything else to beat it). Part of it is exactly the depth that it develops with the extra ‘time to grow’. There are a lot of other excellent parts though.

I actually bought this one in hard copy. Don’t forget to read the typesetting note …

First novel I’ve experienced with a “cookie credit”. Read the typesetting credit for your cookie.

I stalled on it when some new character was put in danger. *shrug* But I might go back to it just because I’m jonesing for the last Locke & Key trade. I’m surprised you wrote this. You seem to prefer writing shorter books.